I thought AI, Artificial Intelligence, was a supportive assistant. I may have been very wrong.

I thought AI, Artificial Intelligence, was a supportive assistant. I may have been very wrong.

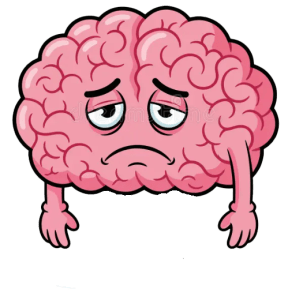

In short, AI could be eroding your brain’s capability. Using your brain less, helps you become brainless…meaning as you use AI more and more, you use your brain less and less. This results in the brain losing its power and potency.

Read the following research results to understand how your brain capability is diminished by AI and digital devices.

__________________

How Technology Is Reshaping Our Brains

The ChatGPT Brain Study

MIT researcher Nadia Kosmyna conducted an experiment using electroencephalograms to monitor brain activity while participants wrote essays with varying levels of digital assistance. The results were striking: those using ChatGPT showed significantly less brain connectivity and reduced activity in networks associated with cognitive processing, attention, and creativity. When asked immediately after submitting their work what they had written, barely anyone in the ChatGPT group could recall anything. The study revealed a fundamental problem—while people felt they were thinking, brain scans showed minimal cognitive engagement.

The Friction Paradox

Kosmyna identifies a core tension: our brains need friction to learn and develop, yet we’re evolutionarily programmed to seek shortcuts. Technology companies have designed “frictionless” user experiences that eliminate the cognitive challenges necessary for learning. This has led to a cascade of dependency—we avoid phone calls, rely on apps for simple calculations we could do mentally, use GPS on autopilot, and reach for our phones to check facts before trying to remember them ourselves.

Signs of Cognitive Decline

The convenience comes with concerning costs. PISA scores measuring 15-year-olds’ abilities in reading, math, and science peaked around 2012 across developed countries. IQ scores, which rose throughout the 20th century, now appear to be declining in many developed nations. Teachers worldwide report that students produce passable AI-generated work without understanding the underlying material, raising concerns about a generation losing essential critical thinking skills.

The “Stupidogenic Society”

Education expert Daisy Christodoulou suggests we may be entering a “stupidogenic society”—parallel to an obesogenic society where it’s easy to become overweight—where it’s easy to become intellectually passive because machines can think for us. As we deepen our dependence on digital devices, we find it increasingly difficult to work, remember, think, or function without them.

Continuous Partial Attention

Tech consultant Linda Stone coined this term in the late 1990s to describe the stressful state of trying to juggle multiple cognitively demanding activities simultaneously. Her research found that 80% of people experience “screen apnea” when checking emails—becoming so absorbed they forget to breathe properly. This constant state of hypervigilance makes us more forgetful, worse at decision-making, and less attentive, while creating only an illusion of productivity.

The Design Problem

Our digital devices aren’t built to help us think clearly—they’re designed to capture and monetize our attention. The internet has become an information desert where junk content dominates, much like food deserts in obesogenic societies. “Brain rot,” Oxford’s 2024 word of the year, captures both the mindless feeling from scrolling through low-quality content and the corrosive nature of that content itself.

The Historical Perspective

Critics note that similar concerns have emerged with every major technological shift. Socrates worried that writing would weaken memory and create only “the conceit of wisdom” rather than true understanding. Yet writing, printing presses, and the internet ultimately democratized knowledge and made humanity more innovative. Humans excel at “cognitive offloading”—using tools to reduce mental load and achieve more complex tasks. AI already helps scientists discover drugs faster and doctors detect cancer more efficiently.

The Central Question

If technology truly makes us smarter, why do we spend so much time feeling intellectually diminished? In the era of AI-generated misinformation and deepfakes, how will we maintain the skepticism and intellectual independence we need? As Kosmyna warns, AI companies are pushing products onto the public before we fully understand the psychological and cognitive costs. By the time we recognize our minds are no longer entirely our own, how much of our capacity for independent thought will remain?

________________________

Richard’s response

AI is a tool I use increasing each week. Time is important to me as I age. I recognize my time is decreasing and am reminded that as I approach my 80’s, my time is getting shorter. Therefore I look for ways I can save time or mazimize the time I am now using.

AI is my assistant of choice. I could do many things on me own, without use of AI and I might find satisfaction in doing so know I am using my own brain. However, much of the work I do takes time, time to create, time to write, time to edit, time to rewrite and time to review. AI saves me time doing in seconds what would take me significantly longer, likely hours. Add up all my time researching, writing and refining my work and you end up with hours of time taken. AI does all this for me in minutes, if not seconds.

I check AI’s results where I think I should. I know it occasionally screws up, giving me inaccuracies or hallucinating as it is called. But more often, it seems to produce factual information that is acceptable.

Considering the saving of time, the speed of results again saving me time, I’m doubtful I will pass on the use of AI. I begrudge that my work takes so much time but sometimes I prefer me to IT. This whole commentary was written by me….now let me show you AI’s version of the same thing….

_____________

Author’s Note: The preceding 650 words were composed without artificial intelligence, requiring approximately 45 minutes of focused work. The exercise serves to illustrate precisely the trade-offs under discussion.

Now, permit me to present an instructive comparison: AI’s rendering of these same arguments…

The AI version…

On the Pragmatic Adoption of Artificial Intelligence: A Personal Perspective

My relationship with artificial intelligence has evolved from cautious experimentation to strategic reliance, with usage intensifying weekly. This trajectory is not driven by technological enthusiasm alone, but by a stark mathematical reality: at nearly eighty years of age, I face the most fundamental constraint any human confronts—the finite nature of time itself.

The arithmetic of aging concentrates the mind wonderfully. Each passing year represents not merely a marker of longevity but a diminishing reserve of productive hours. This awareness has fundamentally altered how I evaluate any activity that demands my time and cognitive resources. The question is no longer simply “Can I do this?” but rather “Is this the most judicious use of my remaining time?”

AI as Cognitive Infrastructure

I have come to regard AI not as a replacement for human thought, but as essential intellectual infrastructure—comparable to how previous generations adopted calculators, word processors, and search engines. Could I accomplish my work without these tools? Certainly. Would there be a certain satisfaction in knowing that every word, every calculation, every revision emerged solely from my own cognitive labor? Perhaps. But such satisfaction would come at an extraordinary cost.

Consider the typical workflow for substantive written work: initial research and information gathering, conceptual organization, first-draft composition, structural editing, stylistic refinement, fact-checking, and final review. Even a modest project can consume four to six hours when executed entirely through traditional methods. AI compresses this timeline dramatically—not by eliminating the intellectual work, but by serving as an accelerant to processes that previously demanded disproportionate time investments.

What once required hours now takes minutes. What once required days can be accomplished in hours. This is not merely convenient; it represents a qualitative transformation in what becomes possible within the constraints of a human lifespan.

The Question of Accuracy and Verification

I am not naive about AI’s limitations. The technology demonstrably produces errors—what researchers term “hallucinations”—generating plausible-sounding content that proves factually incorrect upon examination. I have encountered these failures myself and have developed protocols for verification, particularly in domains where accuracy is non-negotiable.

However, it is worth noting that human cognition is also fallible. Our memories distort, our biases color our interpretations, our attention lapses. The relevant comparison is not between perfect AI and imperfect human thought, but between two imperfect systems—one of which operates at vastly greater speed.

Through systematic spot-checking and selective verification, I have found that AI produces acceptable, factually grounded results with sufficient frequency to justify its continued use. When errors occur, they are typically identifiable through basic scrutiny. The efficiency gains vastly outweigh the modest investment required for quality control.

The Irreversibility of Adoption

Given these considerations—the compression of time, the acceleration of output, the acceptable accuracy rates—I find it highly improbable that I will abandon AI tools. The cost-benefit analysis is simply too compelling. To revert to purely manual methods would be to voluntarily accept a dramatic reduction in productive capacity during the years I have remaining.

This is not to say I have relinquished all preference for unassisted work. There are projects where the process itself holds value, where the slow, deliberative work of composition serves purposes beyond mere output. Writing remains thinking, and there are thoughts that only emerge through the friction of wrestling with language oneself.

Indeed, this entire commentary represents exactly that choice—a deliberate decision to compose without AI assistance, to demonstrate that the capability and preference for independent work remain intact. But having made that choice, I can attest to the time it has consumed.

__________

What’s your thinking about all this?